SKOCH Summit

Agenda

0915 - 1000

Inaugural Session

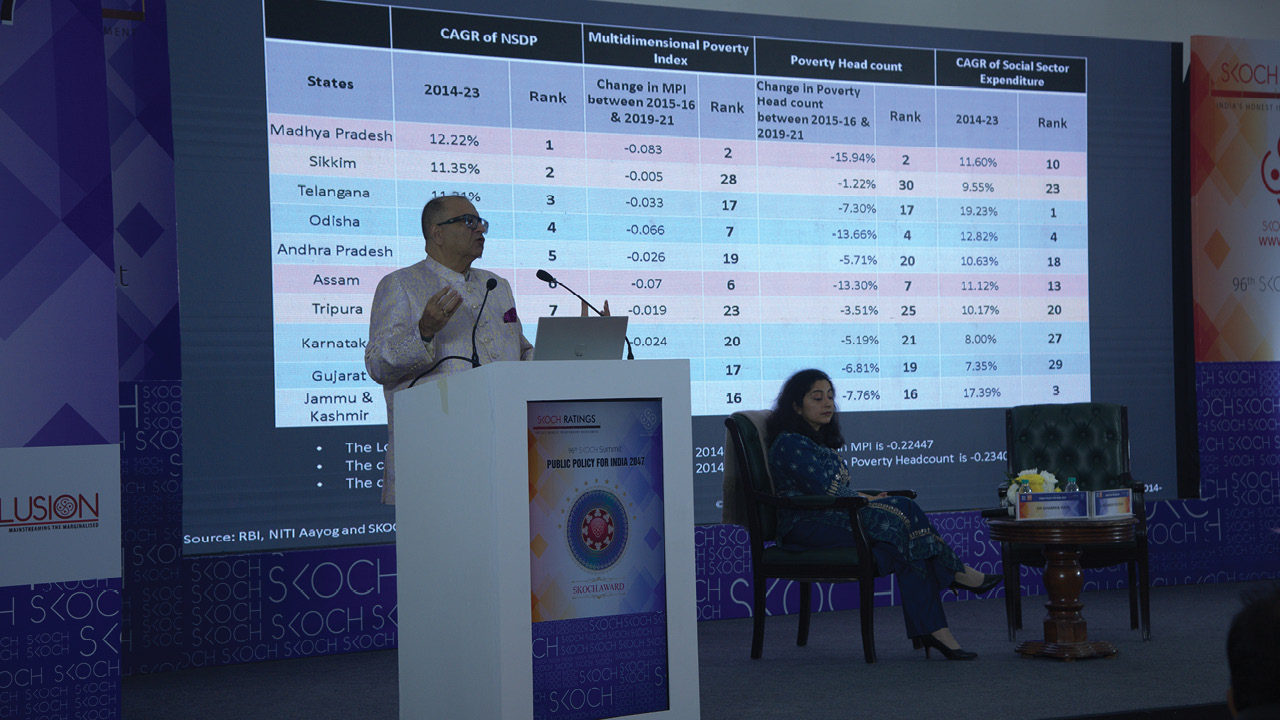

Summary: The address outlined SKOCH’s 25-year journey in advancing inclusive growth through evidence-based public policy. Drawing from personal experience of poverty, he emphasized the Prime Minister’s vision of India 2047 as a developed, poverty-free nation. He explained that inclusive growth rests on three pillars—digital, financial, and social inclusion—and highlighted India’s progress in each over the last decade. The speaker critiqued the limitations of official statistics and stressed the importance of qualitative, project-level research. He presented data showing that all Indian states have grown economically since 2014, with no state left behind. He underscored that GDP growth alone does not eliminate poverty; equitable distribution and access to credit are crucial. SCOCH’s independent research, financial deepening analysis, and governance indices were showcased as reliable tools for policymaking. He concluded by reaffirming the need for spatially dispersed, job-generative, and equitable growth to achieve India’s 2047 goals.*

1000 - 1020

The Science of Public Policy

Public policymaking is considered an art and a science. In India, it has traditionally been more of an art and less of a science due to the lack of an adequate statistical knowledge base. We were also quite late in starting with measuring outcomes. It is only with the administrative reforms kicked in over the past decade and the success of Digital India that intense monitoring and dashboarding is in place.

India is again on a manufacturing-in-high-gear approach for various reasons. This conversation has three central themes. One is changing the defeatist mindset of people who argue that India has no future in manufacturing. The same argument has been rehashed since the 1980s. Geopolitical as well as industry lobbies drive this. Some historical events driving these arguments would be the signing of WTO, the signing of ITA, and more recently, the argument in favour of China-led RCEP.

The second is knowledge-based policymaking. All sorts of proxies are used to support arguments. These are more based on allegiances and opinions rather than sound public interest. The statistical system needs an overhaul. In India. What can be done? And finally, the a lack of wide sharing of the ground covered in governance. The type of administrative reform and cutting of the red tape to deliver development objectives is unprecedented. The softer areas that yield inclusivity and reduction in multi-dimensional poverty have been a high priority.

Mr Sameer Kochhar, Chairman of SKOCH Group, tries to find answers to these in conversation with one of the sharpest development economists of our time, Dr Shamika Ravi, Member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister.

Dr Shamika Ravi, Member, Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister in conversation with Mr Sameer Kochhar, Chairman, SKOCH Group

Summary: The session opened with Mr Sameer Kochhar introducing Dr Shamika Ravi and framing the dialogue around the “science of public policy.” Dr Ravi argued that policymaking needs representative, high-quality, real-time data, and that India’s traditional survey systems are often too slow for a rapidly changing economy. She explained how new sources like satellite imagery and global datasets can complement government statistics, especially for issues like “hidden urbanization.” The discussion highlighted that poor data and weak expertise can lead to confident but incorrect conclusions, making better analysis as important as data collection. The conversation then shifted to manufacturing, rejecting the “defeatist” view that India can skip manufacturing and move straight from agriculture to services. Dr. Ravi emphasized manufacturing’s role in jobs, geopolitics, and strategic self-reliance, noting global moves toward industrial policy and reduced dependency. Trade and RCEP were discussed in terms of balancing openness with protection of vulnerable livelihoods, such as dairy farmers. The session concluded by reinforcing that India must stay globally engaged while building self-reliance in strategic sectors like food, defense, energy, and electronics.*

1210 - 1230

The Big Hardware Push

Tech pioneer, Dr Ajai Chowdhry – commonly known as the Father of Indian Hardware – believes that policy push around manufacturing has set a fertile ground for transforming the country into a global powerhouse for electronics and semiconductor production. The conversation revolves around how a timely push has or will help the country grab a massive opportunity in the electronics hardware space. There is need to upgrade India to a product nation rather than focusing only on manufacturing.

How to make India Atmanirbhar in electronics, from design to manufacturing is what remains at the core of conversation between Dr Chowdhry and Mr Sameer Kochhar.

Dr Ajai Chowdhry, Co-Founder, HCL in conversation with Mr Sameer Kochhar, Chairman, SKOCH Group

Summary: The session explored India’s largely forgotten hardware legacy and its deep link to the rise of the software industry, with Dr Ajai Chowdhry and Sameer Kochhar arguing that India was a serious hardware manufacturing and exporting nation in the 1980s–90s, not merely a “screwdriver” economy. They highlighted how import restrictions and IBM’s exit forced Indian firms like HCL to design computers, operating systems, and electronics end-to-end, creating engineering capabilities that later powered India’s software boom. The discussion traced how policy missteps, grey markets, and global trade agreements weakened domestic electronics, leading to today’s heavy import dependence. Both speakers challenged the narrative that India should focus only on software, stressing that hardware and software are complementary and strategically critical. They concluded that India must move from a services-led model to becoming a product and manufacturing nation, with semiconductor fabs and hardware self-reliance seen as essential for long-term economic and geopolitical resilience.*

1240 - 1300

Make In India - AI For The World

India stands at the forefront of the AI Revolution. The country leads the Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence and champions responsible and ethical AI policies, addressing themes like Sustainable Agriculture and Collaborative AI. India has the potential to add $1.2 Tn to $1.5 Tn to its cumulated GDP between 2023-24 to 2029-30 with the potential to add $359 Bn to $438 Bn in 2029-30 alone. The conversation focuses on factors for making AI in India for the world that hinges on it’s compute capacity. Leveraging AI prowess through collaborative approach addressing global challenges while ensuring responsible AI adoption within the country is an important part of the discussion.

Mr Rohan Kochhar in conversation with Mr Abhishek Singh finds out how AI impacts the job market and how India can ensure a smooth transition through reskilling and upskilling initiatives to remain a competitive talent hub for AI-related jobs while promoting inclusive growth.

Mr Abhishek Singh, Additional Secretary, MeitY in conversation with Mr Rohan Kochhar, Public Policy Professional

Summary: The session featured Rohan Kochhar in conversation with Abhishek Singh, Additional Secretary, MeitY, on India’s strategy to emerge as a global AI leader. Singh emphasized that India’s strength lies in its AI talent base, while data governance and compute capacity are the key gaps being addressed through major public investments and private-sector partnerships in supercomputing. He outlined plans to build indigenous large language models trained on Indian datasets and languages, supported by robust privacy-preserving data-sharing frameworks. The discussion highlighted India’s shift from a services-led economy to a product- and innovation-driven one, enabled by PLI schemes and Digital Public Infrastructure like UPI and Aadhaar. Singh also explained India’s approach to AI regulation focused on safety, trust, and user protection without stifling innovation, alongside large-scale reskilling initiatives to make the workforce AI-ready. The session concluded with India’s vision to lead the Global South by enabling equitable access to AI compute, data, and skills through global collaboration.*

1405 - 1435

Policy For Promoting MSME's

The role of MSMEs cannot be denied in making India Aatmanirbhar by 2047. Union Budget 2023-24 has earmarked Rs 22,138 crore for the MSME ministry, around 41.6 per cent higher than the preceding fiscal year. It presents a financial plan to address financial needs of the MSMEs. These businesses are recognised as the growth engine of the Indian economy as these contribute around 30% of India’s GDP and provide employment to more than 110 million.

There are strong headwinds from the global economy that may impact the small businesses, which contributed more than 45% to India’s exports last fiscal. There is need to conduct an impact assessment of the institutions and policies over the last couple of decades to help fresh thinking that may help mitigate the crisis and layout the path to 2047.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) can emerge as a transformational force for MSMEs in e-commerce that may boost profits and make them more competitive. On the other hand, there are innovations using ML and AI enabling quicker and more informed lending decisions suitable to their credit needs.

The panel discusses the implications of the budget announcements, how to address their need for access to credit and how can the current institutional mechanism be improved to help strengthen the MSME sector.

Mr Anil Bhardwaj, Secretary General, FISME & Dr Saibal Paul, Associate Director, Sa-Dhan in conversation with Dr Gursharan Dhanjal, Vice-Chairman, SKOCH Group

Summary: The session brought together Dr. Gursharan Dhanjal, Anil Bhardwaj (FISME), and Dr Saibal Paul (Sadhan) to examine why India’s MSME sector—despite employing about 110 million people and contributing roughly 45% of exports—remains largely unorganised and perpetually constrained. The panel debated the ₹20,000+ crore budget support for MSMEs, arguing that headline allocations matter less than whether funds directly enable large-scale technology upgradation, which they said currently receives little to no dedicated support. Bhardwaj traced MSMEs’ competitiveness challenge to post-1991 exposure to global competition amid technological obsolescence, calling for deeper financial-sector reforms and revival mechanisms for sectors still lagging after a K-shaped COVID recovery. Paul stressed that the hardest problem is last-mile finance for “nano enterprises,” where documentation, collateral, credit guarantees, and suitable insurance products remain major barriers, even as microfinance reaches millions. The discussion highlighted the crucial role of state governments in fixing zoning and building bylaws so informal, home-based enterprises can register, access finance, and enter formal support systems—potentially doubling district GDPs in a few years. Emerging technologies like AI and IoT were seen as both productivity boosters and exclusion risks, raising concerns around interoperability, portability, and data privacy alongside the need for awareness and affordable funding for adoption. Equity financing was described as underused because going public demands transparency and compliance that many small firms avoid, contributing to the “dwarves” problem where MSMEs refuse to scale. The panel proposed a dedicated, pan-India MSME-focused commercial institution with direct lending, full banking services, stronger credit guarantee mechanisms, and more practical parameters, concluding that with the right reforms India could lift growth from 5%+ toward 7–9% and better align MSMEs with the 2047 development ambition.*

1505 - 1525

Rethinking Markets

The bullish narrative for the country’s stock markets has gathered momentum as economies, geopolitics and policy have all aligned in its favour. The maturing of Indian stock markets is leading to increase in competition. It is important that there is level playing field for all the players. The conversation revolves around the theme of Rethinking Markets and includes how to make Indian markets more vibrant, safe and even more competitive. There is need for a connect between the real economy and markets. Similarly, it is important to de-risk the markets, widen the product portfolio and encourage more and more players. Additionally, there is also a need for MFs to bolster their presence on the exchanges equally to deepen liquidity.

Dr Gursharan Dhanjal, Vice-Chairman, of SKOCH Group tries to find answers to these and more in a conversation with Mr U K Sinha.

1525 - 1545

Let's Talk Financial Literacy

We work hard to earn our money. But regardless of how much we earn, the money worry never goes away. Then the question arises, wouldn’t it be wonderful if our money worked for us just as we worked hard for it? What if we had a proven system to identify dud investment schemes? How to get a simple, jargon-free plan to get more value out of our money for tomorrow (insurance) and have a good life today as well? At the core remains something that we call sound financial planning that requires financial literacy. An important element of it is the cost of financial literacy and who would bear this cost?

Dr Gursharan Dhanjal converses with Ms Monika Halan, according to whom the answers in managing cash flow, building emergency fund, investments and retirement lie in financial literacy.

India’s most trusted name in personal finance, Monika Halan offers you a feet-onthe-ground system to build financial security. Not a get-rich-quick guide, this book provides you a smarter way to live your dream life, rather than stay worried about the ‘right’ investment or ‘perfect’ insurance. Unlike many personal finance books, Let’s Talk Money is written specifically for you, keeping the Indian context in mind.

Ms Monika Halan, Author in conversation with Dr Gursharan Dhanjal, Vice-Chairman, SKOCH Group

Summary: The session focused on the importance of financial inclusion and financial literacy in a maturing Indian capital market. Ms Monika Halan emphasized that true inclusion goes beyond bank accounts to building financial stability and informed decision-making. She highlighted the shift of financial responsibility from the government to individuals after economic liberalization and the critical role of education in managing risk. The discussion stressed starting with safe, government-backed savings products before moving to risk-based investments like equity and mutual funds. Mutual funds and index funds were presented as sensible, diversified avenues for retail investors. The role of regulators, educators, and transparent products in protecting investors was underscored. The rise of retail participation in markets was seen as a positive demand-driven change. The session concluded with a strong call to embed basic financial education in school and college curricula for long-term impact.*

1600 - 1620

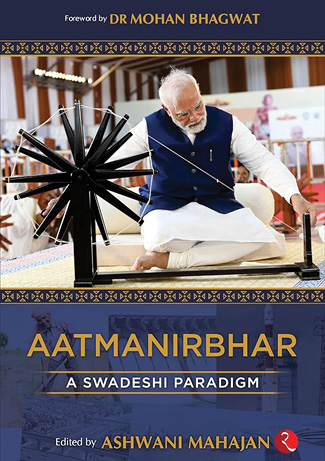

A Swadeshi Policy

India's approach to globalisation over three decades ushered in a surge of companies that contributed to their respective countries' prosperity, simultaneously deepening India's reliance on overseas supplies. The pandemic laid bare the severity of this situation, highlighting the weaponisation of global instruments, particularly in the international payment system and the supply chain for essential materials. The growing influence of global powers caused many nations to lose confidence in the concept of globalisation.

At this pivotal moment, Prime Minister Narendra Modi issued a resounding call—the AatmaNirbhar Bharat Abhiyan.

This new vision for self-reliance diverges significantly from earlier approaches. It centers on adopting best practices for global production while concurrently cultivating domestic capabilities to reduce dependence on imports. According to Prof Ashwini Mahajan, this strategy incorporates a blend of innovative measures, including production-linked incentive schemes and government-backed technological support. He is in conversation with Mr Sameer Kochhar and talks about a practical framework for revitalising industries impacted by inexpensive foreign goods.

Dr Ashwani Mahajan, National Co-convenor, Swadeshi Jagran Manch in conversation with Mr Sameer Kochhar, Chairman, SKOCH Group

Summary: Dr. Ashwini Mahajan argued that India’s development historically came from society and private enterprise, not a state-driven economic model. He criticized Nehru-era policies for discrediting private enterprise and creating the license–quota–inspector regime that blocked competitiveness and exports. He said India’s global trade share fell sharply from 1950 to 1980 due to high tariffs and quantitative restrictions, and that liberalization without adequate preparation worsened the balance of payments. He identified China’s WTO entry in 2001 as a turning point that led to large-scale dumping, rising import dependence in APIs, electronics, and telecom, and a decline in manufacturing’s GDP share. He supported raising tariffs and using protective measures to rebuild domestic industry, citing improvements in electronics production and reductions in trade deficit after such steps. He framed Aatmanirbhar Bharat as restoring India’s older strengths—relying on domestic resources, skills, and youth—while selectively using foreign help where needed. He emphasized self-reliance in strategic sectors like defense and highlighted India’s progress in defense production/exports and space achievements. On electronics and component duty cuts, he acknowledged current dependence on China for essential inputs but claimed India can end this dependence within five years through domestic capacity building.*